TODAY (February 20) marks the birthday of one of the most famous and respected social reformers of the Victorian age.

The Reverend Benjamin Waugh dedicated his life to making the world a less cruel place for children.

He was the founding father of one of the largest and most successful charities in British history - the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) and although he was originally from North Yorkshire, before moving to London and then Hertfordshire, Waugh chose to spend his final years right here in Southend and in fact, is buried in the town’s Sutton Road Cemetery.

Waugh was born on February 20, 1839 in Settle. His father James was a saddler and his mother, Mary, was known around the town as “the Good Samaritan”. She was considered to be a selfless woman committed to giving her children a charitable and Christian upbringing. Tragically she died when Benjamin was only eight-years -old but her son clearly inherited his mother’s compassion. When he was just a boy he demonstrated this when he carried out one of his first acts of benevolence.

It happened in his home-town of Settle when the local constable put two boys before the magistrates’ bench for stealing a turnip in order to make a jack-o-lantern.

Despite his young age Waugh went before the bench to appeal for leniency for the boys and stressed that he too had committed the same offence, but had not been found out.

Later he attended theological college in Bradford before moving to Newbury in Berkshire, where his first pastoral role again saw him yet again fighting against the harsh prosecution of a child for the ‘crime’ of stealing turnips.

Waugh made a speech to the court in the boy’s defence and he succeeded in stopping the youngsters from being jailed.

Waugh then moved to London and it was while he was working as a congregationalist minister in the slums of Greenwich, that he became appalled by the conditions he saw children being exposed to,

Working in the slums exposed him to the cruelties suffered by the poorest in society. He soon created a church and founded a “Society for Temporary Relief in Poverty and Sickness” and set up a day home where working mothers left their children.

He abhorred the workhouse system which saw children as young as five being sent down mines, up chimneys or working in dangerous conditions in factories. In 1873 he wrote a book entitled The Gaol Cradle, Who Rocks It? which called for the creation of juvenile courts and children’s prisons as a means of diverting children from a life of crime.

In his book Waugh outlined the trials of children aged from six to 14 for the most trivial of offences - including taking bread, sweets or fruit or letting off fireworks, all which meant a jail sentence. In 1875 there were 7,173 children in prison in England and Wales - 927 of them were under 12.

The National Archives have a number of documents proving that youngsters at this time were sent to prison for the most trivial of offences. Among the historic charge sheets held by the archives is that of 11- year- old offender John Greening from Mortlake in London who was sentenced to one month hard labour in 1873 for stealing a “quarter of growing gooseberries” in Richmond. The charge sheet list the boy as 4ft 4 inches tall with a grey eyes and the distinguishing feature of a scar upon his forehead. He had several previous convictions for stealing coal - no doubt in a bid to simply keep warm - and had been jailed three times before. He had also received the punishment of being whipped for his past transgressions.

Youngsters like John Greening were exactly the types of children that Waugh wanted to help. More and more children were being orphaned and ended up living on the streets. Some were forced into prostitution, while others sought shelter in sewer pipes

Those who were fortunate enough to have a home weren’t always safe either. These youngsters were often sent - by their parents- to work in factories in hazardous situations for 14 to 18 hours a day.

Others would be put to work as chimney sweeps and would come out of the chimney covered from head to toe with soot. Their arms, legs, elbows and knees would be bleeding, only to be washed off with salt water and sent up another chimney.

Waugh just couldn’t stomach these injustices. In 1884, he was a co-founder of the London Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (echoing a similar initiative in Liverpool), which was launched at London’s Mansion House on July 8. Five years later, with Waugh as its first director and Queen Victoria as its first patron.

In another of his books: Some Conditions of Child Life in England, published in 1889, Waugh described his disgust as the sexual abuse of children: “It will be impossible to even mention the hosts of those special defilements and injuries done to girl children,” he wrote.

“They are vast in number and incredible in kind, and include large numbers of own fathers as the fearful criminals.”

He also described the violent abuse often meted out to youngsters by their own parents.

“There was the poor little boy of seven, the hated encumbrance of a father and stepmother, bound and sometimes gagged and thrust in an orange box - unfed all day long in a locked-up room,” he said.

He also touched on the notorious Victorian practice of ‘baby farming’ where youngsters would be fed chalk and coal and then left to starve - or drowned - in order to spare their parents the cost of feeding them.

Waugh described his horror at one example of this - the “immersing of a dying boy in a cold tub for an hour ‘to get his dying done’”.

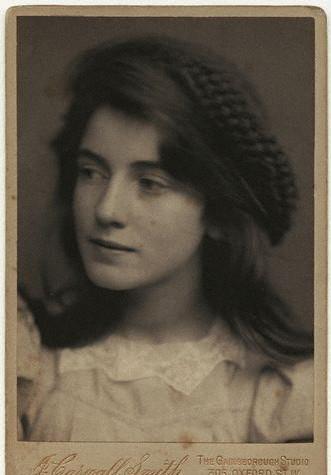

Waugh and his wife Sarah Elizabeth had 12 children including a daughter, Edna, who would become a notable watercolour artist and draughtsman and most famous for providing the illustrations to Emily Brontë’s blockbuster novel Wuthering Heights.

In 1905, Waugh retired to live at 4 Runwell Terrace in Westcliff where he died three years later.

He spent his final years in ill health and had travelled extensively to find a cure. He had grown to love Southend after becoming frequent visitor during his time in London, and had often come to the borough to speak at rallies and meetings to establish a local child-protection groups.

Today his legacy is as a man who who convinced the British public that cruelty to children actually existed and that it was even widespread. He also became instrumental in establishing laws that gave authorities to power to step in and remove children from abusive homes.

Before Waugh, Britain was described as a “much crueller place”. Phillip Noyes, the NSPCC’s director of public policy, has said of Waugh: “He argued that, in England, children were not as well protected by the state as animals.”

“Prosecutions for cruelty to animals had been taking place for 60 years.

“To make the point, he paraded children in animal blankets – what would now be considered a photo call – to show the public that children were really suffering.”

Kind words about Waugh - who refused to accept a salary for his work with the NSPCC -also featured in an obituary which appeared in the Southend Telegraph upon his death on March 11, 1908.

The tribute described how Waugh was known among the poor of Greenwich as a man “who would shrink from no pains to translate his love for children into action.”

“His appeal was almost always met with the answer“there is no child cruelty in this town,” read the obituary “but with his persistence, eloquence and charm of character he gradually succeeded in changing public opinion.”

Such was his determination is tackling the injustice to children that his supporters would often say he was on the “Waugh-path” as he battled the authorities to change laws.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel