The debris in the burnt out shell of Southend’s New Empire theatre packs layer upon layer of history.

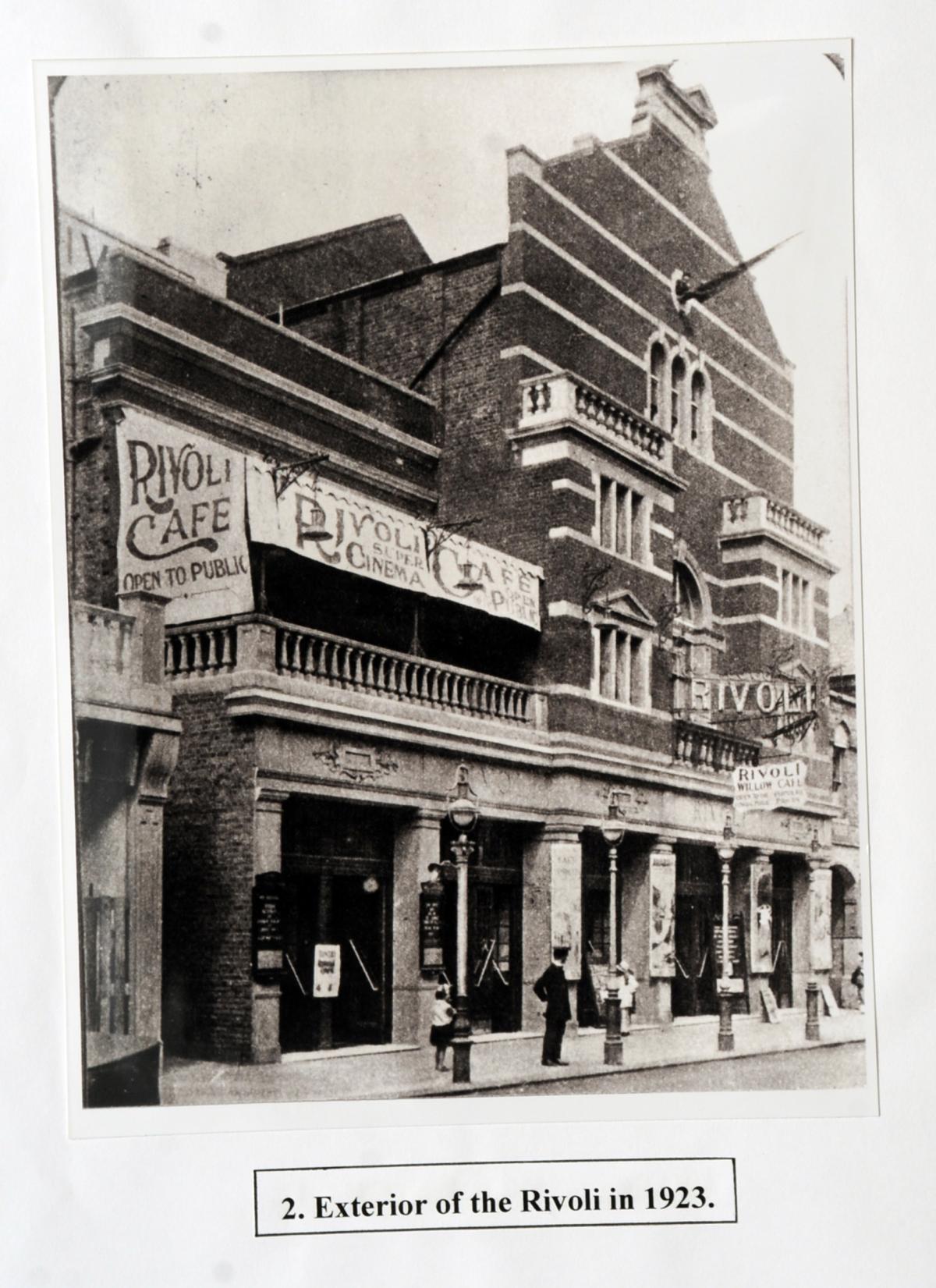

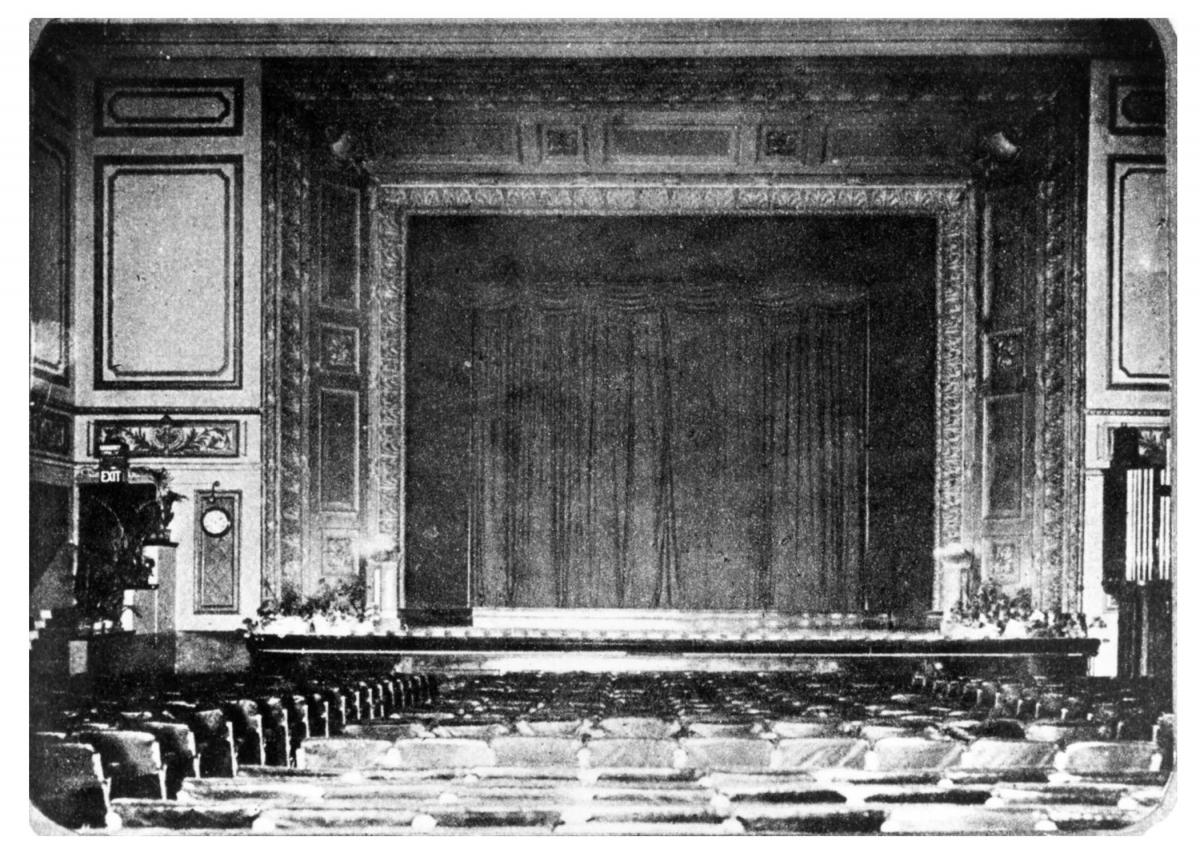

The old building served as a music hall, theatre, and cinema, before reverting to live theatre in 1998. Probably its finest hour was as the sumptuous Rivoli cinema, Southend’s poshest picture palace, between 1920 and 1936.

Music hall, theatre and cinema periods all contributed some extra architectural feature to the building, bits of which now lie as charred remnants piled on the stalls floor. All of these stages have been preserved in photographs.

But for the most part, we only know about the building.

What of the people who lived and worked at the old Rivoli – the usherettes who spent their working life in the darkness, the projectionists in their lonely booth among the piles of celluloid cans, the managers, elaborately dressed in tuxedos even in the early afternoon?

For the most part the names and voices of these people, mostly anonymous, have faded forever. One voice remains, however, to give us a vivid account of life at the picture palace.

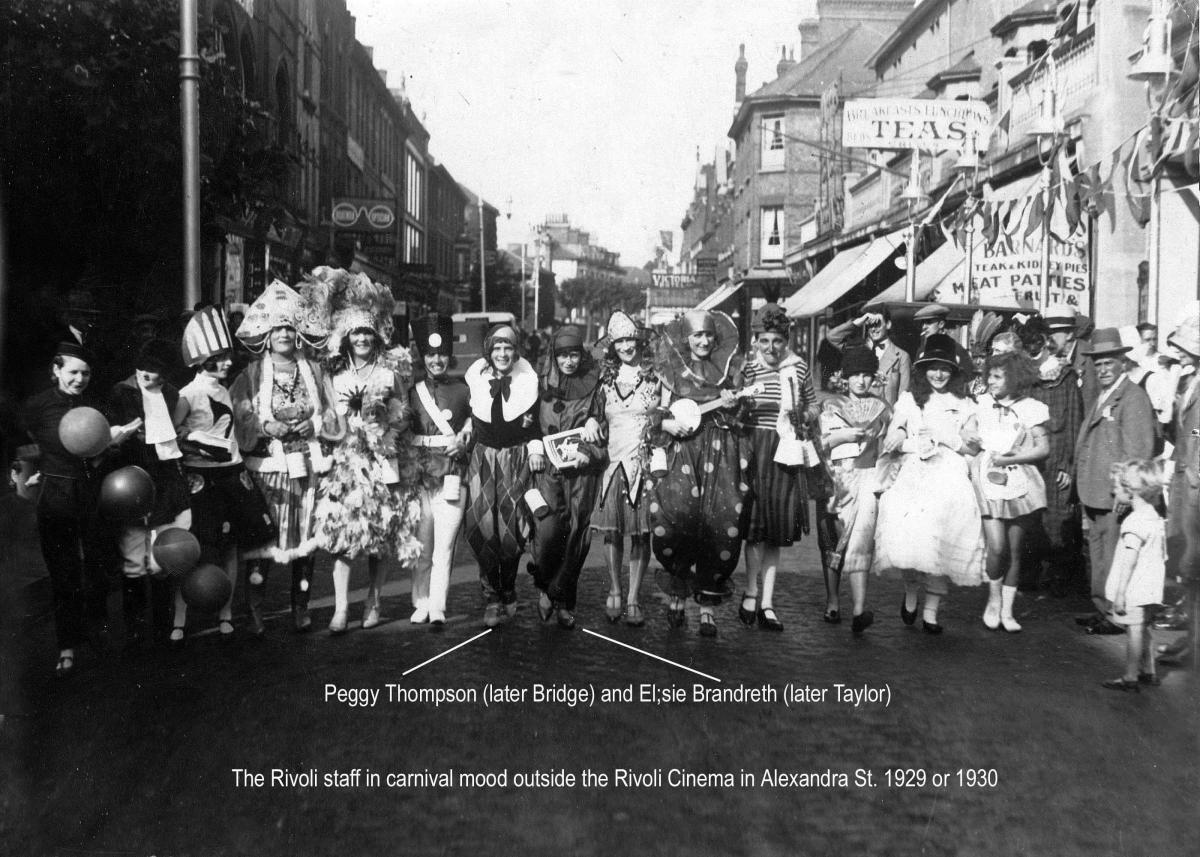

Peggy Bridge (nee Thompson) worked an usherette at the Rivoli in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

While there, she became close friends with another member of staff, Elsie Brandreth, later Elsie Taylor. The bond of friendship lasted for the rest of their lives, staying firm through marriage, children and widowhood.

Peggy died in 1997. But just months before she passed away, Elsie’s son Chris Taylor, a keen amateur film-maker and cineaste, persuaded her to set down her reminiscences of the Rivoli on video. Chris says: “My mum never talked about the Rivoli. Now I realise there are so many things I should have asked her. After she died in 1995, I was determined to get a record of Auntie Peg before it was too late.”

Chris has also discovered a picture, never published before, that captures something of the close-knit family atmosphere among staff at the old Rivoli. It shows members of staff outside the cinema, dressed up for the 1930 Southend carnival.

“You can see they had fun together,” says Chris.

This is confirmed by Peggy.

“I loved my life at the Rivoli. It was happy, it was bright, it was cheerful,” she says in the film.

“I had five happy years and many adventures while I was there.” She also was proud to work in a luxury cinema. “You had to be someone who was specially recommended, not just anyone could work there,” she says on the film.

She remembers the huge crowds which formed when the cinema showed Southend’s first ever talkie, The Broadway Melody, and the time when the cinema was invaded by thousand of mice (“Ooo, I was paralysed with fright”), and the Italian lady organist, Celeste Barra, nicknamed Bumpy Annie on account of her plumpness, who rose and descended at the keys of the cinema’s Wurlitzer organ.

Her main memory, however, is of the manager, Mr Luscombe, “a handsome man in his Forties, always beautifully dressed” and randy as a rabbit.

Peggy puts it more delicately.

“He had a little thrill now and again with one or two ladies.

He could not keep his hands off girls.” He received short shrift, however, when he tried it on with Peggy. She was in the act of closing a curtain when Mr Luscombe picked her up from behind by the waist, crying: “now I’ve got you.”

Peggy said firmly: “Mr Luscombe, put me down. Such a thing I have never heard of. I shall have to do something if you keep on pestering me. I just do not like it. I am not that sort of a person.”

“More’s the pity,” said the manager.

The Rivoli seems to have resembled the set of a Ray Cooney farce as Mr Luscombe’s pretty young wife kept arriving unannounced in the hopes of ambushing him in flagrante.

Peggy found herself acting as look-out. “It was lucky I was fleet of foot,” she says. “I saved his honour.” But Peggy herself refused to let her standards slip. “I never did anything I shouldn’t.”

Peggy’s other prominent memory is of the time that she saw the Rivoli’s ghost, glimpsed many times before and since in one of the old theatre boxes. He is thought to be the spirit of a Victorian fireman who died in a fall from the roof in 1895. “His head was over on one side and he’d got a bandage around it. You could see the blood.”

Peggy’s descriptions help to bring the poor old ruined building alive once more in the imagination, and it is not hard to imagine the ghosts of fat Bumpy Annie and lecherous Mr Luscombe wandering the ruins alongside the bloody Victorian fireman.

Peggy, though, did not linger.

She left the cinema when she married her husband, George.

The Rivoli’s final role in her life was as the base for romance. Like so many young couples at the time, they conducted much of their courtship in the back row of the stalls. “They were able to do so, because staff got free seats,” says Chris.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel