ONE day, Brightlingsea was an ordinary seaside town - quaint, industrious and with a sense of community.

The next it was a battleground.

A storm had been brewing over the export of live animals from British ports and suddenly Brightlingsea was thrust into the national spotlight.

It became the centre of protests over the live exportation of cattle and sheep and battle lines were drawn between protesters and police.

Crowds of people, including students, pensioners and children as well as animal rights activists, gathered every day to express their displeasure at the live exports.

From January until October 1995, they turned out day after day to try to stop the lorries reaching the town’s port.

They hoped to see a ban on the transportation on live cargo, as had previously been won at Shoreham in Sussex.

The protestors used a number of different tactics to try to keep the lorries at bay.

An out-of-town visitor attending the protests for the first time when they were at their height in February 1995 recounted how people formed human chains.

“The plan was to use tactics used by the No M11 Link Road campaigners and Greenpeace activists in other countries,” they said.

“The road would be blocked by a tripod made from scaffold poles, erected hastily when the trucks arrived.

“From the tripod would hang a lone activist while other activists would chain themselves to the uprights and each other.

“Unfortunately someone grassed up the plan and the location of the equipment.

“The police removed the poles and the plan was ruined.”

That day, February 10, the activists instead formed a human chain across the road, sporting a cord and carabiner clip around their wrists.

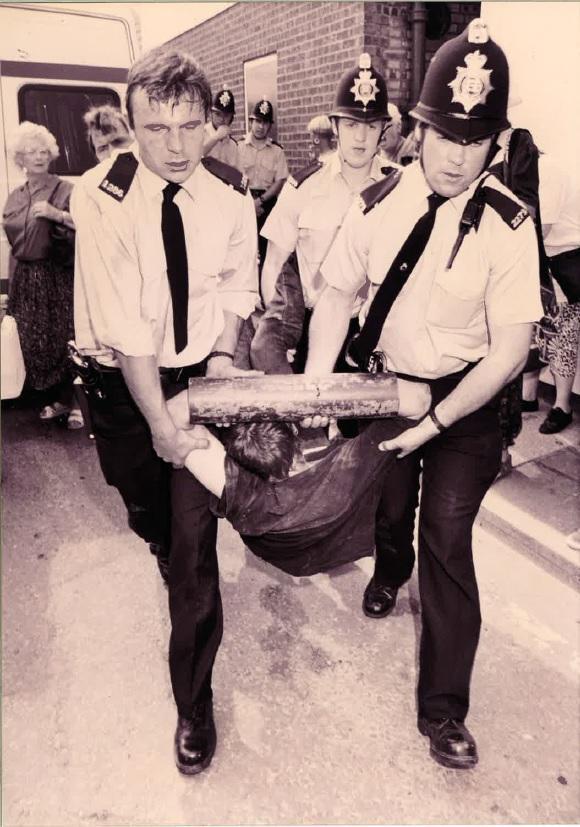

They then inserted their arms into metal pipes and hooked on to each other.

But the police managed to cut their way through the chain.

The protester recounts: “The police went through the rest of the protesters quickly.

“They would step over a row of sitters, then police behind would pluck out each person in turn.

“The trucks were then brought through. There were seven or eight.

“All but one were full of sheep, the other was calves.

“One truck was stacked four layers high. It was emotional, I felt helpless to do anything and the animals would look into my eyes.”

They added: “As the protest reached the port, police tempers flared and one officer lashed out at a protester with a punch.

“Some other incident resulted in an ambulance being called for a protester.”

The police’s force support unit was drafted in to manage the activists.

They were kitted out in full riot gear and carrying batons. The situation had escalated.

The first lorry carrying live animals for export arrived in Brightlingsea on January 16.

Richard Otley, who at the time was Britain’s best known exporter of sheep, had his Range Rover mobbed by the activists during some of the first protests.

Maria Wilby was one of the founding members of Brightlingsea Against Live Exports, an organisation which still meets to this day.

She talks of how the protests galvanised people both locally and nationally.

“They were not involving local police officers,” she said. “They had learned from things like the miners’ strike.

“They came in with body armour and batons, it certainly wasn’t what we were used to in Brightlingsea.

“But just as shocking for everyone was the treatment of the animals.

“You cannot over emphasise how much hurt people felt and how shocking they found it.

“Many police officers could be seen crying.”

Maria was arrested eight times during the protests, while her husband was arrested and charged with assaulting a police officer.

He was later represented by Labour leadership hopeful and renowned Human Rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer in court.

The cost of policing the daily protests reached £3 million.

The transportation of animals was moved overnight for a short while, but by October 18 the lorries stopped coming and the activists had won a hard-fought victory.

But things were far from over for several protestors.

A group - known as the Brightlingsea 14 - were taken to the High Court by farmer Roger Mills - the main exporter.

He tried to sue them each for £1 million for stopping his trade. The action failed.

Mrs Wilby is keen to point out BALE never took an “anti-farmer” stance.

“The protests were not solely about animal welfare,” she said.

“We had speakers from all organisations like the NFU, we did not go down the angle of pushing one point of view.

“Most people made up their mind that they just didn’t like the trade.”

Almost 600 people were arrested as a result of the protests, in what came to be known in the media as the Battle of Brightlingsea.

The protests influenced the way people thought about the meat trade which still resonates today.

“Our local Co-op started getting in a lot more stock,” said Mrs Wilby.

“They changed their stock so it was more free range and organic. People really did begin to explore the issues.

“Part of our mission was to inform people and explain some of these issues.

“The longer they keep an animal travelling, the more money they can make. The most dreadful time for an animal is when they are loading and unloading but the only way farmers could survive was to use this subsidy.

“People in Britain do not pay adequate money for their meat. We rely on cheap imports and forget the value of homegrown products.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel