“LET us not forget the scale of aggression by human beings or the appalling holocaust.”

Those were the words of John Powell Davies in a remarkable interview he gave to the Gazette just months before his death in October 2004, at the age of 84.

Mr Powell Davies clearly wanted to emphasise the trauma experienced by many, at the hands of Nazi Germany during the Second World War, and he would have known how that felt.

John Powell Davies spent four years incarcerated in Colditz, perhaps the most infamous Prisoner of War camp in Europe in the Second World War.

Mr Powell Davies was one of the youngest prisoners, captured aged 19, when the plane he was flying was shot down over Boulogne harbour.

Mr Powell Davies had been sent to drop mines in Boulogne harbour, but German soldiers were waiting for him as he waded ashore.

He was taken to Germany and spent five weeks in hospital before he was questioned. A month later he was taken to the Baltic coast and the prison camp.

Today, as the human sacrifices made during the Second World War and other conflicts are remembered, those who knew John have paid new tributes to the man who not only survived Colditz but who was also a gifted and much-admired Maths teacher in Colchester for nearly 20 years.

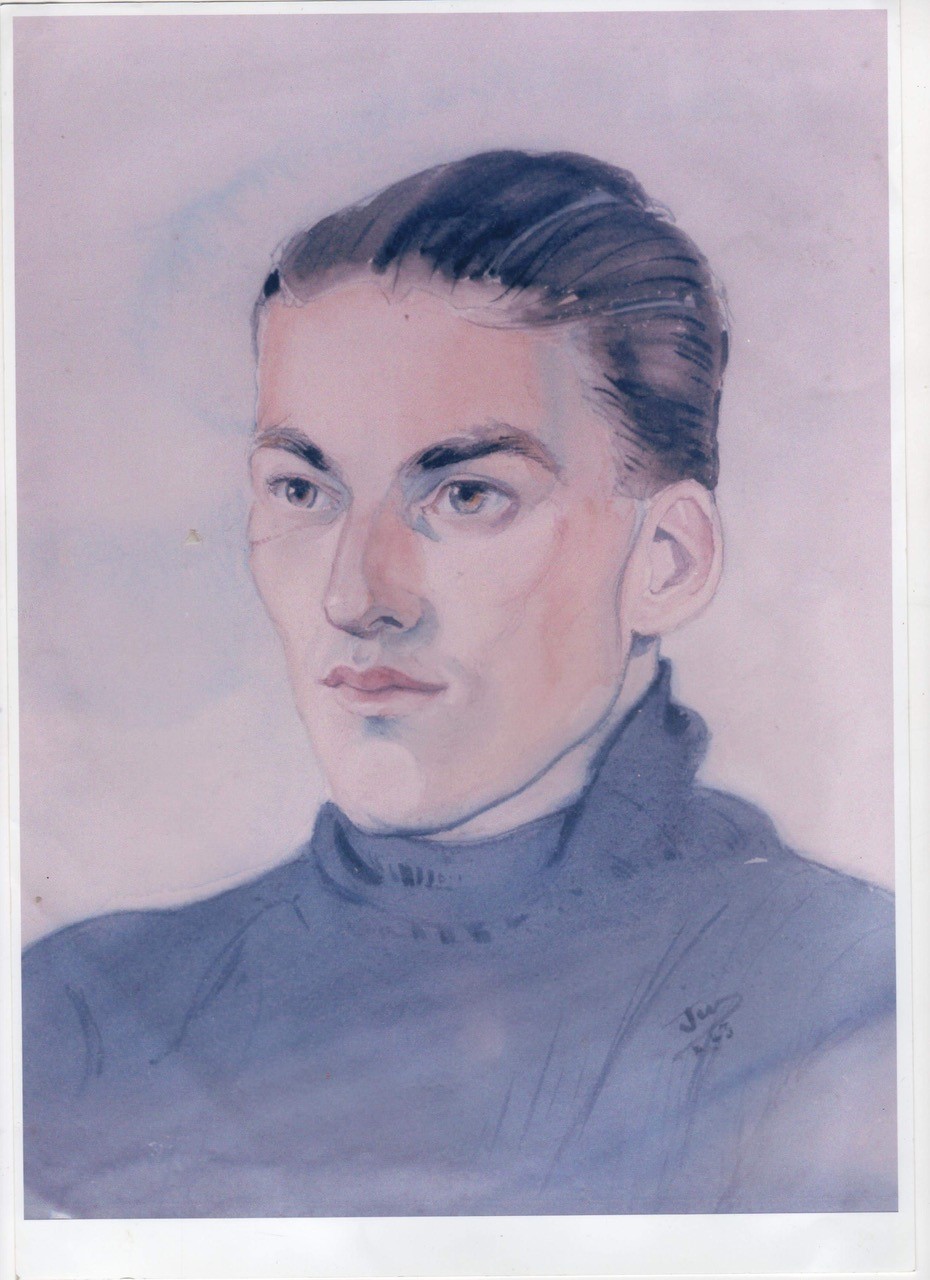

A previously unpublished portrait of Mr Powell Davies painted in Colditz by a fellow inmate

Among them is Professor James Raven, Fellow of Magdalene College, Cambridge, who was a former student of Mr Powell Davies at the Gilberd School.

“John Powell Davies managed to interest even innumerates like me in mathematics”, he said.

“This was partly because of his patience and the clarity of his lessons (aided by his infectious enthusiasm for a new model of slide-rule), but much more by his extraordinary presence in the classroom.

“His authority was certainly helped by his stature.

“His formidable beard and glasses accompanied a voice which you felt should have been booming but was, in fact, powerfully quiet and slow-paced.

“But more than this, even young teenagers recognised they were being taught by a remarkable man - softly spoken with a powerful frame, but also (long before any of us learned of his wartime experiences) with a sensitivity, even vulnerability, that made him trusted and respected in equal measure.

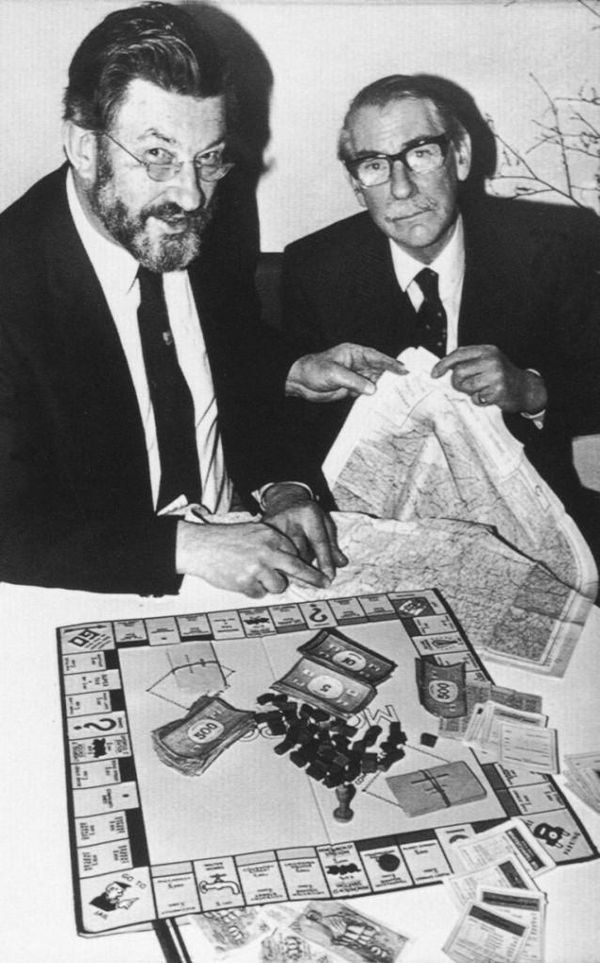

A 1985 Associated Press photo that accompanied the story about him joining Monopoly's 50th anniversary celebrations

“I recall a parents’ evening when instead of showing any interest in me he attended only to my father, immediately recognising a fellow soul scoured by the past.

“Looking back, one remembers John Powell Davies with even greater respect and admiration and what a privilege it was to have known him.”

Mr Powell Davies started teaching at Colchester Royal Grammar School in 1967, before he moved to the Gilberd School in 1972, and he retired in 1986 when it finally left the North Hill site.

The description of Mr Powell Davies the teacher, is a far cry from the emaciated 24-year-old who on April 20, 1945, walked out of Colditz to freedom, weighing just nine stones, 7lbs, yet 6ft 4ins tall, when American forces liberated the camp near the end of the war.

Towards the end of the war, his diet had consisted mainly of boiled kohlrabi and starving Mr Powell Davies would sneak into the kitchen and steal the peelings.

In his 2004 interview, he recalled: “I did get involved with escape plans and was active throughout my four years in supporting those escapes, but I never attempted to escape myself. I hated tunnels.”

During those four years, Mr Powell Davies wrote regularly to Rosemary, the woman who was to become his wife.

Rosemary was a long-serving volunteer with Colchester Samaritans and director of the branch between 1979 and 1984 and died in 1999.

The couple had four sons.

Inmates famously accessed doctored Monopoly games sets which contained smuggled maps, money and steel files, and it was in 1985, the year of the game’s 50th anniversary, that Mr Powell Davies was invited to celebrate with the manufacturers, Waddingtons.

In later life he was an active member of the Colditz Society, often known as the Monopoly Club because of the hidden escape materials.

On returning to England, he married Rosemary in his naval uniform, the only suit he had.

He then took up a previously offered Cambridge scholarship, eight years late, to study engineering, then at age 35, embarked upon his career as a Maths teacher.

His son, Mark Powell Davies, former head of the Colne Housing Association, described how teaching was “central to his father’s life”.

He said: “When I was young he was reluctant to talk about the war and his time in Colditz, as the memories were clearly too raw.

“However, with the passage of time he felt more comfortable with telling some of the stories, presenting awards on behalf of The Colditz Society and going into my son’s primary school to let the pupils know what the war was really like.”

He added: “His career took several turns - actuary, engineer, industrialist - but he really found his calling when he took up teaching maths in his forties.

“I had some first-hand experience of his enthusiasm for the subject when he taught me for a couple of years at Colchester Royal Grammar School.

“He always insisted on addressing me as ‘Powell Davies’ in lessons.

“When I returned to Colchester in my forties I was forever being asked ‘Are you John Powell Davies’s son?’ by ex-pupils who remembered with affection being taught by him.

“He was a keen Rotarian and was a founding member and the second president of one of Colchester’s Rotary clubs leading many of their activities and fundraising events.

“He found important friendships in his relationship with members.

“After retirement, John and Rosemary moved to Mersea. He had holidayed there as a boy, and had always hankered after living by the sea. He was again involved in local life - the Friends of the Museum, the Probus club etc.

“John lived a life of many parts - pilot, engineer, family man - but teaching was a real calling and central to his life.

“He loved mathematics and he loved being able to impart his knowledge and enthusiasm to the pupils who taught.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel