SILENCE fell over the central hall in Southend High School for Boys, as it has every year at 11am on November 11, for the past nine decades. All eyes were facing the south wall and the names inscribed on it.

Normally the roll of honour gets little more than a passing glance, if that. The gold-lettered, wooden boards are just part of the background of teeming school life. But as always on Remembrance Day, they were the focal point.

The silence preceding 11/11/11 is an unchanging ritual. Its lack of variation is a sign that later generations are keeping their pledge to remember.

For this school, though, the 90th anniversary of the Armistice was marked by a departure from the normal pattern. A curtain covered part of the roll of honour.

Shortly before the bell sounded for the two-minute silence, the curtain was pulled back, unveiling a change. After nine decades of lying unacknowledged in a foreign field, two further names had joined the list. Paul Hilleard and Frank Osborne have come home.

Both men’s deaths were a microcosm of the horror and waste of the war that ended 90 years ago. Paul, a fine cricketer, was shot through the eye by a machine gun bullet, near Arras, in April 1915. Frank died from wounds three years later, defending the railhead of Amiens against the last ferocious German onslaught of the war.

Paul was 21, Frank 27, two typical sacrifices. Both were volunteers. They were young men with every reason to want to live, yet they were prepared to die.

Neither though, were added to the roll of honour at their old school. In the case of Paul, the reasons are unclear, since he was a well-known cricketer in the town.

Frank was a trainee teacher at the school, whose links with the school have only just been clarified.

Now, though, in the words of current headmaster Robin Bevan: “Paul Hilleard and Frank Osborne have been thanked properly.”

The names, in gold lettering and a typeface to match the others on the list, have been painted in seamlessly. It would take the eye of a Sherlock Holmes to detect the one discrepancy, they are out of alphabetical order. The late honour finally paid to Paul and Frank comes as the result of a research project conducted by history teacher Lesley Iles, working with her brother John Baker and volunteer researchers, students from the current Southend High generation.

The team has worked together to tell the stories behind the names on the roll of honour.

Lesley says: “Now they are no longer just names. Now we can know something about them as people.”

The student researchers have clearly been affected by what they discovered.

Ben McNish, 18, says: “Some of the people were younger than me when they were killed, as young as 16. It brings home what Remembrance Day is all about.”

The roll of honour is a static memorial, but connection with the Western Front and the generation who died on it is a dynamic thing.

Each year, tens of thousands of children visit the graveyards of the Somme and Flanders. A non-stop run of books and TV programmes indicates the growing interest in that great, terrible war. Far from withering to nothing, as Siegfried Sassoon thought that it would, our awareness is constantly on the increase.

Mr Bevan brought alive the link in a different way, as the school prepared to unveil the names of Paul Hilleard and Frank Osborne. Immediately before the two-minute silence, the headmaster drew attention not to silence, but noise.

Laughter, chatter, games, jokes, the normal sounds of school life were going all around the hall.

He said: “It would have sounded just like that when Paul and Frank were here. That is what they left behind. I think it is superbly fitting we should be listening to it now.”

And then came the silence.

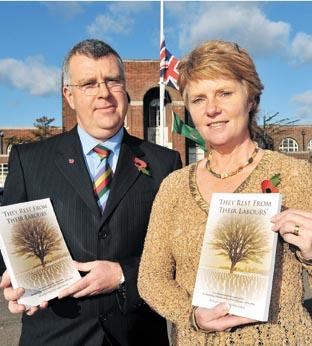

Siblings collaborated to capture lost generation: BROTHER and sister collaborations are a rarity in the book world, but the process worked well for Leslie Iles and John Barber.

The pair teamed up for the first time to research the names of Southend High School’s lost generation, the young men, sometimes boys, whose names figure on the school’s First World War memorial.

The ultimate result of the collaboration is a book, They Rest from their Labours, which brings alive the Southend fallen, as individuals.

Long before this project, brother and sister shared an interest in the First World War. Both were members of the Western Front Association, which keeps records, co-ordinates research and organises battlefield trips.

Neither count themselves as professional writers or researchers. Lesley teaches at the school, John is a manager at the Basildon tractor plant. It was out in the field, among the myriad graveyard crosses of the old battlefields, they found inspiration and came up with the idea of a research project to localise the conflict.

As Lesley points out, the fatalities from just one school in one town are a miniature portrait of the war.

“It’s hard to grasp the scale of the conflict as a whole, but if you look at a cross-section of individual cases, it is a way to understanding,” she says. “Every battle, every sector, every type of warfare is represented among the names in the book.”

Lesley and John segmented their research so each of them was responsible for two years of the four-year war, and different sections of the armed services.

Eventually, the pair may embark on a parallel project covering the Second World War.

“We really need to wait until papers are released 75 years after the war,” Lesley says. Meanwhile, the pair would like to hear from anyone with papers or photographs about people who fought in either war and had a connection to Southend High School for Boys.

Even the First World War book, according to John“is still just a work in progress”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article